A fading black and white photo shows children in Gbarnga, Liberia mugging for my camera in 1965. Life wasn’t easy– check out the head loads. But as adults these children would be thrown into Liberia’s Civil Wars, and life would get much worse. Many would not survive.

Earlier, I blogged about my experience as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Liberia, West Africa during the 60s. While life for tribal Liberians was tough at the time, is was about to get worse, tragically so. You can read about my two years in Liberia by going here and scrolling forward. Presently, I am reworking the posts into book format. In addition to having my book professionally edited, I have added several chapters. Hopefully the final product will reflect what I believe were two of the most interesting years of my life.

The book ends with my leaving Liberia, but I decided to add an epilogue that reflects what has happened in the country since. The Tragedy of Liberia, after editing, will become the epilogue. There are four parts in this series.–Curt

On April 22, 1980, thirteen Americo-Liberians were driven down to Monrovia’s Barclay Beach in a VW van, tied to telephone poles, and shot without blindfolds. One soldier was so drunk he couldn’t hit the man he had been assigned to kill. Afterwards, the bodies were stacked in a pile and sprayed with bullets before being tumbled into a mass grave. It marked the beginning of a tragedy that would see the death of over 200, 000 Liberians.

The international press was invited to witness the event. The names of those executed were a who’s who of Liberia’s history. Their fathers, grandfathers and great grandfathers had ruled the country for period of time stretching back over 150 years.

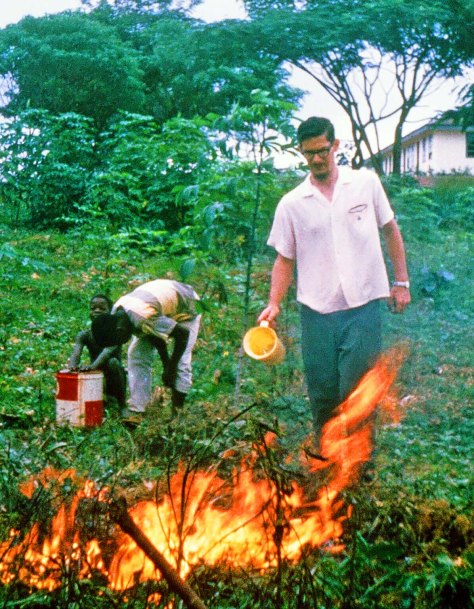

The public executions were as savage as they were inexcusable. But they were also understandable, possibly even inevitable. Thirteen years earlier I had talked into the small hours of the morning at my home in Gbarnga with a representative from the US State Department about the future of Liberia. One of his first requests was that Sam, the young Kpelle man who worked for us, not be present.

Revolution of some kind, I had argued, was going to happen unless drastic changes were made in how Americo-Liberians ruled Liberia. Five percent of the population owned the majority of the nation’s wealth and controlled 100% of the political power. Tribal Liberians were widely exploited and treated as second-class citizens, or worse. Deep resentment was building; a time bomb was ticking. It would explode unless Americo-Liberians were willing to share economic and political power.

I was not optimistic. I related my experiences with setting up a student government at Gboveh High School and in writing a Liberian second grade reader. My goals had been moderate. I wanted my high school students to learn about democracy and my elementary students to increase their reading skills. I certainly was not involved in revolutionary activity. I was merely doing what Peace Corps Volunteers had been brought into the country to do: help educate and train Liberians for the future.

The drastic reaction of Americo-Liberians to my efforts reflected the deep paranoia that existed within the ruling class. The second grade reader, which featured folktales and stories about tribal children pursuing such common activities as playing soccer, was regarded as a revolutionary tract– not because it was anti-government, it wasn’t, but because it didn’t emphasize the Americo Liberian perspective. Even though Peace Corps staff had received initial approval from the Department of Education and arranged an editor, curriculum specialist and graphic artist to work with me, I was directed to abandon the project and never talk about it.

The response to the student government was even more dramatic. My students had decided it would be fun to create two parties to run against each other, like the Republicans and Democrats. Apparently this was a direct challenge to the True Whig Party, the foundation of Americo-Liberian power. Within days, word came down from Monrovia that my students were to be arrested and I was to be run out of the country unless the ‘political parties’ were eliminated immediately.

Americo-Liberians were not stupid, far from it. Many were highly educated and had attended some of the best universities in the world. They knew they were sitting on a powder keg. Change was coming and they could choose to embrace that change and help guide it, or they could resist and fight against it. They chose the latter course. Their power, their wealth, and their privilege were simply too much. They had controlled the tribal population since the inception of the country and believed they could continue to. People who challenged this assumption, even Americo-Liberians who believed that change was needed, were shut down, sometimes violently. Any change would be gradual, even glacial, and would only be allowed with acceptance of the status quo. It was a recipe for disaster.

Tribalism was another issue we discussed on that long ago night in July of 1967 as rain pounded down on our zinc roof, lightning lit up the sky, and thunder rolled across the jungle. When primary loyalty is to the tribe rather than the country, building a modern nation becomes much more difficult. It may also have the impact of dehumanizing people, as I was to learn.

My wife and I were walking home from Massaquoi Elementary School at the beginning of our two-year stint when we found one of our students lying on the ground, obviously very sick. His classmates were walking around him, like he wasn’t there. Jo Ann was furious.

“Why aren’t you stopping to help?” she had demanded.

“He’s not from our tribe,” was the answer. It was a matter-of-fact type statement. The point that he was a fellow human being was secondary.

The problems of tribalism are not insurmountable. I felt my high school students had moved beyond the deeper currents of tribalism. Or I hoped they had. They were proud to be Liberians. Tribal differences were noted with a sense of humor rather than passion. Education, it seemed, could overcome the harmful elements of tribalism.

I expressed one final concern with the State Department official; actually, it was more of a nagging worry. The dark side of juju, or tribal sorcery, lurked beneath the surface in Liberia. Newspapers occasionally included stories about people who had been killed and cut up for their body parts, which were then used in rituals to increase the power of the killer. People were also made sick, or poisoned. When Mamadee Wattee, one of the candidates for student body president, came to my house late one night out of fear that the opposition had obtained juju to make him ill, I took his concern seriously. Every culture has its dark side. Think about the Salem witch trials. Kept in check, such practices have minimal impact. But what if the normal laws and customs of traditional and modern society break down? Would the use of ‘magic’ become more prevalent? And what would be the result?

In 1971, four years after I left Liberia, William Shadrach Tubman, President of the country since 1944, died in a London Hospital. His Vice President, William Tolbert, assumed the reins of power. Tubman had been a master politician with strong connections to both the Americo-Liberians and tribal leadership. Tolbert lacked Tubman’s charisma and leadership abilities.

He did, however, move forward with Tubman’s unification program. Some of the more odious Americo-Liberian customs, such as the celebration of Matilda Newport’s birthday (her claim to fame was mowing down tribal Liberians with a canon), were downgraded or eliminated. The University of Liberia was expanded and improved to provide more tribal youth with an opportunity for higher education. Roads were added throughout the tribal areas. Tolbert also continued, Tubman’s open door economic policy. In a move that ruffled feathers in the United States, he even invited Communist countries to invest in Liberia. The US had long considered Liberia as its African beachhead in the fight against Communism.

In the end, Tolbert’s efforts benefitted the Americo-Liberians much more than they did the tribal population. Extra money invested in the country ended up in the pockets of Americo-Liberians. Roads to interior opened up vast new tracts of land for Americo-Liberian farms. They also provided a way for the government to more effectively tax tribal people.

No one profited more from Tolbert’s actions than his own family. Twenty-two of his relatives held high positions in the Liberian Government and/or on boards of major corporations doing business in Liberia. Wealth accumulated rapidly. The small Liberian community of Bensonville located outside of Monrovia was renamed Bentol in honor of Tolbert and became a family enclave complete with mansion-lined streets, a private zoo and a private lake. The town’s extreme wealth provided stark contrast to Monrovia’s hopeless poverty.

In April of 1979, Tolbert made a fatal error. He arbitrarily increased the price of rice by 50%. Rice was the primary staple of the Liberian diet. The increase meant that urban Liberians would now be spending over one-third of their average monthly income of $80 on rice. Students from the University of Liberia and other dissidents called for a major protest. Police ended up killing a number of the protesters and riots ensued. Tolbert restored order by bringing in troops from Guinea. He shut down the University, rounded up dissidents, and charged a number of them with treason. It was the beginning of the end for Tolbert, and for exclusive rule by Americo-Liberians.

NEXT BLOG: The story of Liberia’s civil wars.